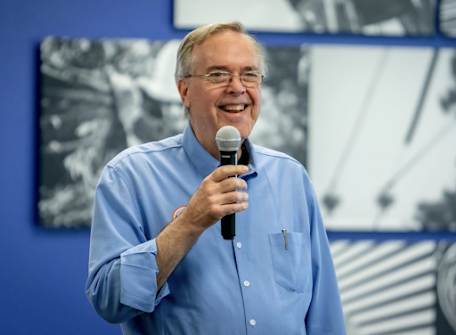

That is Fred Ross, Jr., pictured above. The obituary I have reproduced below ran in the San Francisco Chronicle on Christmas Day, 2022. Clicking on the link I have provided to the word "obituary" will probably get you to a paywall, which is why I have cut and pasted the obituary itself into this blog posting. It's worth reading!

I never knew Fred Ross, Jr., but I definitely knew of him! He was truly a legendary figure in California politics. I am alerting you to his story for two reasons.

First, to highlight Fred's occupational identification:

Ross had a "50-year career as an organizer, the only job title that he would accept."

Second, to highlight the basic technique upon which Ross premised his successful organizing work:

It was a five-year battle that allowed Ross to perfect a simple strategy called the “house meeting campaign” he learned from his father, also named Fred Ross, one of the great community and labor organizers in Bay Area history.

If we want a politics that can make real change, significant numbers of us are going to have to decide that our lifetime work is going to be as "organizers."

If we want to transform our politics, to head off the disasters that are all too visible on the horizon - and that, in fact, are right in front of us, right now - then we need to organize meetings of small groups of people, in real life, to inspire them, and their friends, and those just watching, to change their lives.

As Fred Ross, and Fred Ross, Jr. would tell us, that is the kind of politics that works!

oooOOOooo

Fred Ross Jr., organizer of California labor and political campaigns, dies at 75

December 23, 2022

Fred Ross was a 22-year-old idealist fresh out of UC Berkeley when he

joined the struggle of farmworkers in the “salad bowl strike” against

lettuce growers in Salinas in the early 1970s.

It was a five-year battle that allowed Ross to perfect a

simple strategy called the “house meeting campaign” he learned from his

father, also named Fred Ross, one of the great community and labor

organizers in Bay Area history.

Fred Ross

Jr. (as he was known) would go to the camps and trailer parks where the

pickers lived, in order to gain the trust of the United Farm Workers,

led by Cesar Chavez. A better listener than talker, Ross came up with

the idea of a march from Union Square in San Francisco to Gallo

headquarters in Modesto, 110 miles away.

Some 20,000 made that 1975 march or a portion of it, the end result being the Agricultural Labor Relations Act

signed by Gov. Jerry Brown in June that year to protect the rights to

collective bargaining for farmworkers. That campaign started Ross on a

50-year career as an organizer, the only job title that he would accept.

He gave himself that modest title for Nancy Pelosi’s

first campaign for Congress, in a special election in 1987, and he gave

himself that title during the campaign to face down the attempted recall of San Francisco Mayor Dianne Feinstein, in 1983, and California Gov. Gavin Newsom in 2021.

There were many victories in between, and when Ross turned 75, on

Oct. 14, a video was put together by those who wanted to thank him,

starting with former U.S. Secretary of Labor Robert Reich. The video ran

2½ hours, which is what it took to squeeze them all in. Ross watched it

on a big screen at his home in the Berkeley Hills, where he was

confined due to treatment for pancreatic cancer. He died at home Nov.

20, said his wife, Margo Feinberg.

After his death, letters and statements came in from

dignitaries struggling to express in writing what many of them had said

on the birthday video.

“Fred was a force to be reckoned with and I’m thankful to have called

him a dear friend,” wrote Feinstein, a U.S. senator since 1992. “His

support and leadership as my deputy campaign manager during the 1983

recall campaign was instrumental to my success and I am forever indebted

to him.”

“Without his early support and brilliant leadership

organizing the ground operation of my first campaign, I would have never

become a Member of Congress,” House Speaker Pelosi wrote.

“He moved mountains on behalf of so many communities

and organizations, always keeping our state’s most vulnerable

populations at the top of his mind,” Newsom wrote. “His passion for

equity, inclusion, and justice illuminated his ambitious path, but it

was his tireless determination and work ethic that allowed him to walk

it.”

Frederick Gibson Ross was born Oct. 14, 1947, in Long

Beach and spent his early years in Los Angeles. His father worked at

Community Service Organization on behalf of Latino civil rights. His

mother, Frances Gibson, had been a “Rosie the Riveter” at an Ohio

factory in World War II. She contracted polio after the war, and when

Fred was 5, his family moved to Corte Madera to be near family in Marin

County.

Ross attended Neil Cummins Elementary School in Corte

Madera and Redwood High School in Larkspur. He was elected student body

president for his senior year, and graduated in the class of 1965.

After a year at Syracuse University, where his father was

teaching a course in organizing basics, Ross transferred to UC

Berkeley, graduating in 1970. While at Berkeley, he was involved in the

anti-war protests, though he had a low lottery number and was not

drafted, Feinberg said.

During the People’s Park conflict in

1969, he came to the aid of a protester who was being hassled by

police. That got Ross arrested, one of 39 times he was in his life as an

activist and an organizer. With a record like that, he figured he

needed a lawyer. So he became one in 1980, after graduating from the

University of San Francisco School of Law.

Ross spent two years as a public defender in San

Francisco before giving up the law to become a full-time organizer. That

is the job he had had since his junior year at Redwood High, when he

went to Arizona with his father on a program sponsored by the

Presbyterian church to bring the Yaqui and Mexican American communities

together to fight the poverty both groups faced.

From that point on, it was one campaign after

another. In 1973, when Ross was 26, he was the lead organizer of the Bay

Area grape and lettuce strikes, a battle that would last for years and

involved pickets in front of Safeway and other major grocery chains.

“Fred had this amazing way of engaging in campaigns

that gave you a sense of joy that you were part of moving the needle,”

said Bob Purcell, a retired Sacramento labor attorney who worked with

Ross on the farmworker campaigns.

As that battle was winding down, Ross moved on to

Neighbor to Neighbor, an organization formed in the 1980s to aid the

plight of refugees from El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua. This

evolved into a national campaign to elect people opposed to the

government policies toward Central America imposed under President

Ronald Reagan.

One of these candidates was Pelosi, who hired Ross to run

her field program when she ran for Congress in a special election to

replace Sala Burton, who had died in office in 1987.

Utilizing his house meeting strategy from the UFW

campaign, Ross put together 118 meetings in the San Francisco homes of

Pelosi supporters, who would invite their neighbors to meet the

candidate. In the final frantic days of a tight race, Ross organized 17

house meetings in a 12-hour span, and it got the job done. Pelosi

narrowly won the seat she still holds after 35 years.

“He’s been part of her kitchen cabinet and our

extended political family ever since that first election,” said Pelosi’s

daughter Christine Pelosi, an attorney and advocate who uses Ross to

teach the house meeting technique at her Campaign Boot Camp. The night

after Ross died, both Pelosis went to the Ross home to sit with the

family.

“In a bittersweet bookend, we had a house meeting to

mourn his passing,” Christine Pelosi said. “We were involved in some

very tough political fights and Fred was always there with an effective

strategy and what the farmworkers call animo.”

In 1997, Ross was working for an immigration rights

organization in Los Angeles when he met Feinberg, a prominent union-side

labor attorney with offices in Los Angeles and Berkeley. They were

married on Feb. 15, 1998, at the officers club in the Presidio of San

Francisco with 250 people in attendance. After living on Potrero Hill,

the Rosses moved to the Berkeley hills, where they raised two children,

Charles Ross, 23, and Helen Ross, 20.

Ross spent his last years working on a documentary film

about his father’s organizing legacy, to be directed by Ray Telles. The

on-camera interviews have been completed and Ross was raising funds for

an impact campaign to bring the film into schools, union halls and

community organizations at the time of his death. The film will be

completed in 2023 and the fundraising goes on. Donations in his name may

be made to fredrossproject.org

“Fred was the guy in the back of the room encouraging

others to step forward,” Feinberg said. “He viewed his role as an

organizer as inspiring others to tell their stories and empower

themselves to make change in their community and workplace, and he did

it with enthusiasm and humor.”

She survives him, as do son Charles and daughter

Helen, all of Berkeley; sister Julia Ross of Larkspur; and brother

Robert Ross of Davis.

A public memorial will be held Feb. 26 at Delancey Street Foundation in San Francisco. RSVP is required at fredrossjrmemorial@gmail.com.

Image Credit:

https://ibew1245.com/2022/11/21/ibew-1245-grieves-the-passing-of-brother-fred-ross-jr-and-honors-his-legacy/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for your comment!