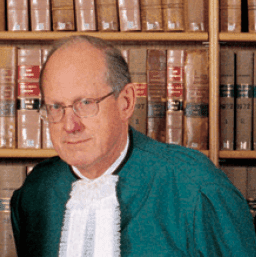

You will be forgiven if you don't immediately recognize former South African Constitutional Court Justice Laurie Ackermann, pictured above. I hunted down the picture because I recently read a paper about Ackermann, authored by Roger Berkowitz, the Founder and the current Academic Director of the Hannah Arendt Center at Bard College.

Berkowitz' paper dates from 2009, and is titled, "Revolutionary Constitutionalism: Some Thoughts on Laurie Ackermann's Jurisprudence." The Berkowitz paper was the first I had ever heard of Justice Ackermann.

In fact, at least the way I read it, Berkowitz' paper is not really about Ackermann's jurisprudence. While the paper begins and ends with some references to Ackermann, the focus of the paper is on how revolution is connected to human (and specifically political) freedom, drawing mainly on the thoughts of Hannah Arendt.

The Berkowitz paper is pretty "academic," and thus might be heavy going for those not familiar with the substance and style of academic writing. It is, however, worth reading, and I have provided a link, for those who might want to read it. My purpose is served by quoting what Berkowitz says near the very end of his discussion:

Arendt sees that the fateful choice to found the legitimacy of modern law in democratic consent is ‘built on quicksand.' It is a solution to the problem of authority that replaces ‘monarchy, or one-man-rule, with democracy, or rule by the majority.’ But democratic rule is, as rule, nothing but the principle of majority decision. Since that democratic decision ‘is ever-changing by definition’ and susceptible to the weakness of wilful demagoguery, the elevation of democratic decision-making to democratic rule harbours a grave threat to the protection of political and human rights and thus to the protection of every limitation and space of freedom.

What I take this to mean is that protecting our right to "vote" for those who will decide what happens to us is no guarantee of political freedom. In fact, and this is a theme deeply embedded in everything Arendt ever said about government, we preserve our freedom only by our personal participation in the discussion that leads to decisions. Electing the people who will then hire the people who will run our lives for us is to have lost what Arendt calls our "revolutionary treasure," which is a life together based on a government of, and by, and for the people - to use Lincoln's words.

It's those "of" the people and "by" the people parts of Lincoln's formulation that are the most important. Without our direct and personal participation in the political process, without our personal involvement in the debate and discussion that leads to decisions, a government that claims to be "for" the people can quickly degenerate into an illegitimate exercise of power by those who happen to have claim to public office.

A concern that this is what has happened to us, here in the United States, is what a majority of Americans probably believe, today, about our national government. Our government claims to be "for" us, but it is not really a government that is either "by" or "of" the people themselves. Thus, whether seen from the perspective of either left or right, our government is not a government that can command any profound respect or allegiance from those who are subject to its decisions.

This is profoundly dangerous, and we are living in dangerous times, as surely we all know. Our personal connection to and participation in the debate and discussion that precedes governmental action is what we need. That's really what a "revolutionary constitutionalism" requires.

Image Credit:

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for your comment!